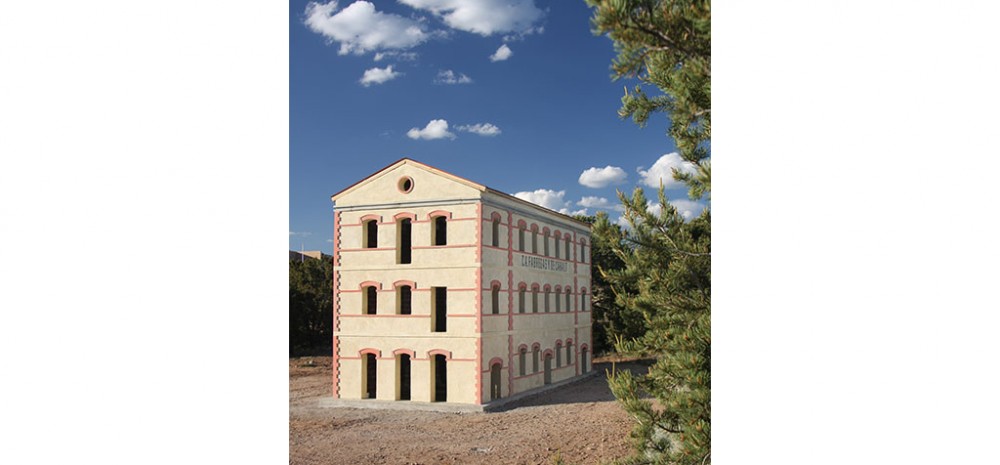

Marti and the Flour Factory, 2008

Brick by brick, Catalan artist Marti Anson wants to construct a copy of a building. This is the story of a 150 year-old industrial building.

The story of the peculiar copy begins a few months ago, when Catalan artist Marti Anson was astonished by the controversy that was stirred up by the proposed demolition of an old flour mill in his home town, and decided to take the building to New Mexico

This is not the first case of the ‘removal’ of a building. Two years ago the so-called ‘Yinyu House’  the Englishman’s house  was transferred from its original location in the Anhui province of eastern China to the Peabody Essex museum in Salem, MA. The house’s 700 blocks of wood, 8,500 tiles, and more than 500 pieces of stone were packed and shipped in 40 containers and duly reassembled in its new home in the US.

There are many other examples of copies being built in the United States and the rest of the world: the replica of the Parthenon in Athens in Nashville, Tennessee; the Pavilion of the Spanish Republic for the 1937 International Exposition in Paris, rebuilt in Barcelona for the 1992 Summer Olympics; the Paleolithic caves of Altamira; the Globe Theatre in London; or the Eiffel Tower. It is enough to drive round Las Vegas to see a huge number of places from all over the world concentrated in a single city.

That is what occurred to the local politicians in a town on the outskirts of Barcelona  to make a copy of one of its old industrial buildings. The construction of a new shopping mall prompted the city government to rethink the urban layout, directly affecting a 19th-century mill. The first decision taken by the town council was to demolish the old building so that the mall could occupy the site, but the response of the local people caused them to change their minds  they came up with the Pharaonic idea of replicating the factory 200 metres down the street from its original location. The grassroots campaign in opposition to the destruction of the factory, Save Can Fabregas, changed its slogan to Save Can Fbregas Where It Is.

The removal and reconstruction of the building is so expensive that the town is waiting to see what will happen. Meanwhile the old mill is still in place, waiting for its future to be decided.

Coming up with absurd initiatives seems to be one of the ‘sports’ of the people of Matar. The people who live there are known as Capgrossos  stubborn. Back in the last century a local fisherman built a boat inside his house, and when he wanted to take it down to the sea it turned out that the only door was smaller than the boat. So the people of Matar are Capgrossos.

A local artist, without giving it too much thought, suggested that the city of Santa Fe might make a copy of the Matar factory, and found that people responded in a very positive way. With the help of Lucky Number Seven curator Lance Fung, Anson outlined the project to Sue Sturtevant and Stuart A. Ashman, from the Department of Cultural Affairs, and to the Mayor David Coss, who welcomed the scheme with open arms.

Anson has taken up the idea as a challenge, and plans to carry out the whole project with his own hands, as an act of faith to save the heritage of his home town. Brick by brick he will build a copy of the original in Santa Fe, and on completion the building will be handed over to the city to take its place among the existing adobe structures.

The copying of large buildings, moving them from one place to another, has become a frequent image of the TV news, which regularly keeps us up to date about the latest records in this new sport. And, as with all sports, the most important thing is taking part, not winning. This project, too, is open to any outcome  time alone will tell.

Marti’s project is located off-site at Museum Hill’s Auxiliary Parking Lot.

Lives and works in Barcelona

Marti Anson’s work typically involves generating expectations in the viewer that are subsequently not fulfilled. In his installations, films, and photographs, something always happens. This unknowable entity, which at times may be instigated by a gesture, idea, or sound, prompts us to think that some other event will soon take place. Like passengers waiting for a train to arrive or a plane to depart, we remain with growing anticipation. But generally, the thing that we foresee happening, which Anson has subtly planted in our minds, never comes about.

Three years ago, at Barcelona’s Centre d’Art Santa Monica, Marti Anson presented his most ambitious project: Fitzcarraldo, 55 days working on the construction of the yacht Stela 34 at the CASM. Throughout the fifty-five working days that the exhibition was open, the artist set about building his yacht. Methodical and meticulous, Anson, in this case, accepted a failure foretold. After many days of building this magnificent vessel, Anson finally finished; however, the boat could not be removed from the gallery intact, as it was intentionally built 4″ wider than the door. And so, as expected from the outset, the boat, which he had put so much effort into building, was destroyed in little over an hour.

Time becomes an integral part of this process. For Anson, things do not change, but rather are constantly recomposed. Many of his works illustrate precisely this: a dislocation of time, of how events transpire ? sometimes, to the point of ridicule. On other occasions, Anson demonstrates how, after patiently waiting and using that period of expectation for analysis, nothing happens.

Marti Anson’s work is situated midway between frustration and enthusiasm, sharing both emotions with the viewer. A meticulous observer of reality, for him, the process is more important than the result, championing above all the value of work in art.

Ferran Barenblit